Ozark Chinquapins with Dr. Fred Paillet // OCANPS Field Trip: 26 April 2025

A preamble to the flowering season of the last remaining trees of the species...

We’re about halfway through the scheduled spring hikes for the Ozark Chapter of the Arkansas Native Plant Society, with today’s hike being a rescheduled one, unsurprisingly one orginally cancelled due to rain— better to have too much of it than too little, right?

Out on a section of the Back 40 trail system in Bella Vista, Benton County, Arkansas, we went out to learn as much as we could about the Ozark Chinquapin tree from Dr. Fred Paillet, adjunct professor of the geosciences department at the University of Arkansas.

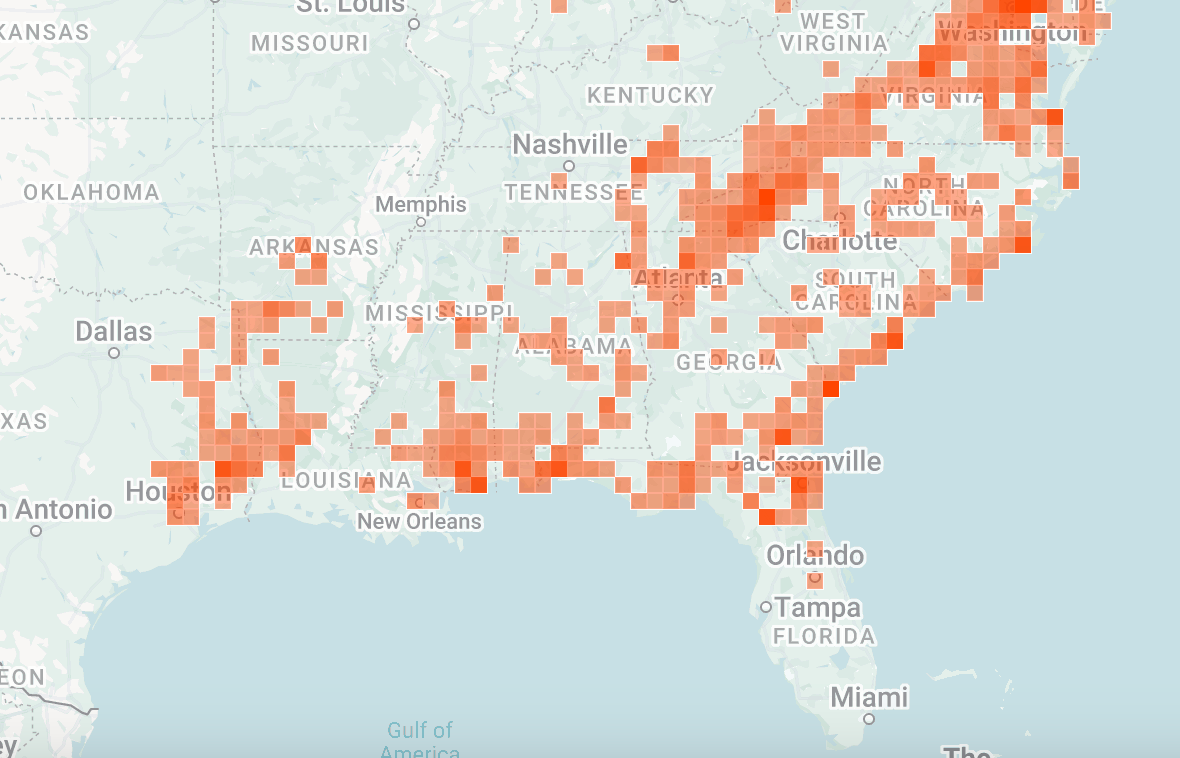

Once common throughout the eastern United States, our native chestnuts— trees in the genus Castanea— have been nearly exterminated by a century or so of devastation from an imported pathogen, the Chestnut Blight Fungus. With an incredibly high kill rate, this fungus has lain waste to chestnut populations en masse across both the US and Europe. It began in the east and spread over time, where it first came to Arkansas in 1957.

In reviewing these photos of old growth chestnuts, I think about an old cypress tree I was once brought to see in eastern Texas, south of the city of Tyler. It was covered in Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), otherwise I would’ve gladly found a way up and climbed that massive stump with a lift— I’ve never seen a tree even half its size. As he commented: it’s probably now just the floorboards in some oversized house in Dallas. And realistically, with the LVP and “millenial gray” trend, that tremendous tree is probably in a landfill somewhere, replaced by glorified plastic flooring.

People know the price of everything and the value of nothing, right?

Although the American Chestnut is not native in our state, we have a few native ‘chestnuts’, including the Ozark Chinquapin (Castanea ozarkensis) and Dwarf Chinquapin (Castanea pumila).

So, how do we know the exact year— 1957— that it arrived?

Dr. Paillet explains that simple process: when the first die-offs began, they would core the trees that were immediately next to the dead chinquapins, then examine the growth rings. These neighboring trees would suddenly have a giant leap in the size of their rings in the year 1958— expanding up to 5x their normal growth per year due to the lack of competition created by the deceased chinquapin.

The logic is simple: if you’re a tree, and a large tree next to you that once cast quite a bit of shade over your photosynthetic leaves wilts and dies… you have access to far more sunlight in its absence.

Your competition upped and left, allowing you to take the lead, growing at an unprecedented pace.

The same results were consistently found across many trees, confirming this conclusion.

These “cookies” cut out of an oak and a chinquapin show an interesting difference in their rings. Oaks have rays, while other species, including chinquapins, do not.

The few trees that we saw today, alive and with leaves but reduced to skinny shrubs, are thought to be seedlings that were established prior to 1957. The blight makes them die back to their roots, where they continue to sprout suckers. Surviving trees are a mere fraction of the size they would be without the invasive blight fungus.

Evidence of the blight is quite clear, even when the sprout hasn’t died (yet). The base of the trunks are cracked, and during particular seasons have the orange sporing bodies of the fungus exposed.

Those that are still hanging on for now often die back after several years, seeming fine for long periods of time only to have their leaves turn brown in autumn and never regrow in the following spring...

And of course, whether it’s caused by clearings created for trails, or by misguided habitat managers who are “thinning” their woods indiscriminately, Ozark Chinquapins are routinely cut down due to negligence. Natural threats persist, too, like the tornado that felled our state champion tree in 2024. The blight isn’t the only thing bothering them.

The nuts of chinquapins were versatile and highly valued in the not too distant past. For our wild animals, chinquapins were a prominent food source; one study from a university in Ohio claimed they produced 100x the nuts compared to Northern Red Oaks (Quercus rubra). Turkeys, White-tailed Deer, and Bobwhite Quail all rely on populations of acorns and other native nuts for fall forage.

As for people, chinquapins were an oft consumed (and free!) snack throughout their native range. They were so common that they were once used in various games by children, serving as dice or other game pieces. Musical instruments like dulcimers have also been made of the wood, which was prized for railroad ties, fences, and other similar uses.

The Ozark Chinquapin Foundation has an entire article of recollections of Arkansawyers who grew up with chinquapins, viewable here, largely through the context of a game called Hully Gully. Their other resources include histories on other uses, the historic and modern ranges of the species, general descriptions, old newspaper clippings that mention the chinquapins, and more. Lots of great information.

From Chestnut Mass, the publication of the Carolinas Chapter of The American Chestnut Foundation:

Chinkapins are very much part of the culture of the South. The small nuts are said to be sweeter than chestnuts. Cherokees, Choctaws, Creeks and Seminoles, as well as southern white and black kids of later years, munched on them like candy, strung them as beads or used them in games.

Of course, being nearly gone now, hardly anyone remembers them.

The Ozark Chinquapin feels especially poignant as a symbol of the disappearing natural spaces of northwest Arkansas. What we see in front of us is so fragmented by human activity that it hardly resembles what once was. Along the highway, the woods are cleared to build houses with large lawns (evidently more important than preserving trees), and the prairie ridges of nearby Pea Ridge are swallowed up by tract housing where not a single native plant exists after developers clear the land and scrape the topsoil off for sale.

Well, after all— who would want something like a majestic Blackjack Oak (Quercus marilandica) to sprawl over their lawn? You would have to blow the leaves off, bag them in plastic, and haul them to an incinerator. Heaven forbid that nature be allowed to persist…

The casings of chinquapins are covered in spikes, making them quite difficult to open should you stumble upon one that is either too early in the season to naturally disperse, or that did not get pollinated and is thus half-formed.

In their proper state, with time the fruits burst open and reveal their seeds.

Early on along the first trail we walked, there was an American Elm (Ulmus americana) with its characteristic shallow roots, especially exposed on this eroded hillside.

Much of the vegetation was ‘weedy’ in nature, but I was pleasantly surprised that it was mostly native— Cornsalad (Valerianella radiata), Velcro Bedstraw (Gallium aparine), and so on. A handful of native wildflowers persisted through the slopes, mostly Two-flower Dwarf-dandelion (Krigia biflora), Wild Hyacinth (Camassia scilloides), and a few Fire Pinks (Silene virginica) here and there as well.

Most of the non-native weeds were minor ones, although I did spot a few Burning Bush (Euonymus alatus) shrubs flowering and a few Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum) stalks sprouting up.

We carpooled to a different section of the trail to learn how to look at chinquapins forensically.

Throughout the acidic woodlands of the Arkansas Ozarks, chinquapins have fallen for over half a decade, large trees slayed by the blight long ago. Their trunks are uniquely resistant to rot— hence their past usage as fencing— and thus they are not only in good shape over the decades they’ve been dead, but very little grows over them and conceals what’s left. This makes them easy to identify decades after they’ve fallen to the forest floor.

The remaining parts of the tree are deeply furrowing, un-eroded by the passage of time.

One hint that a fallen log in the forest is a chinquapin is that it has multiple branches, sprawling even in death. They also generally don’t have anything growing over them except for a few mosses and lichens.

At the end of the hike, all attendees were rewarded with a summary of much of the information relayed today, plus one of Dr. Paillet’s ink illustrations of what these chestnuts would have looked like back in their heyday. He used measurements of fallen logs that he surveyed to draw the most accurate picture possible of them, as they would have been in life.

Although he didn’t mention anything about incorporating drawings into research— even though I asked him if he was familiar with Guyette’s work on Eastern Red Cedars in the Missouri Ozarks, which he was— Dr. Paillet frequently did include illustrations with papers he published! I discovered this while looking for additional sources while writing this article.

I aspire to be able to hand out copies of my own drawings at the end of guided ANPS hikes…

Want to know how to identify remnant Ozark Chinquapins in your area? It’s surprisingly uncomplicated, as far as things in the oak family go.

Chinquapin Identification

Chinquapins and all chestnuts are in the oak family, Fagaceae. Subsequently, they look similar to a few oak species.

There are also a couple of other types of chestnuts that they look similar to— some are native to other state in the US, others are native to Asia. These will only be present in cultivation, although it’s always possible for any species to escape and become invasive. Hybridization is another issue/possibility, too.

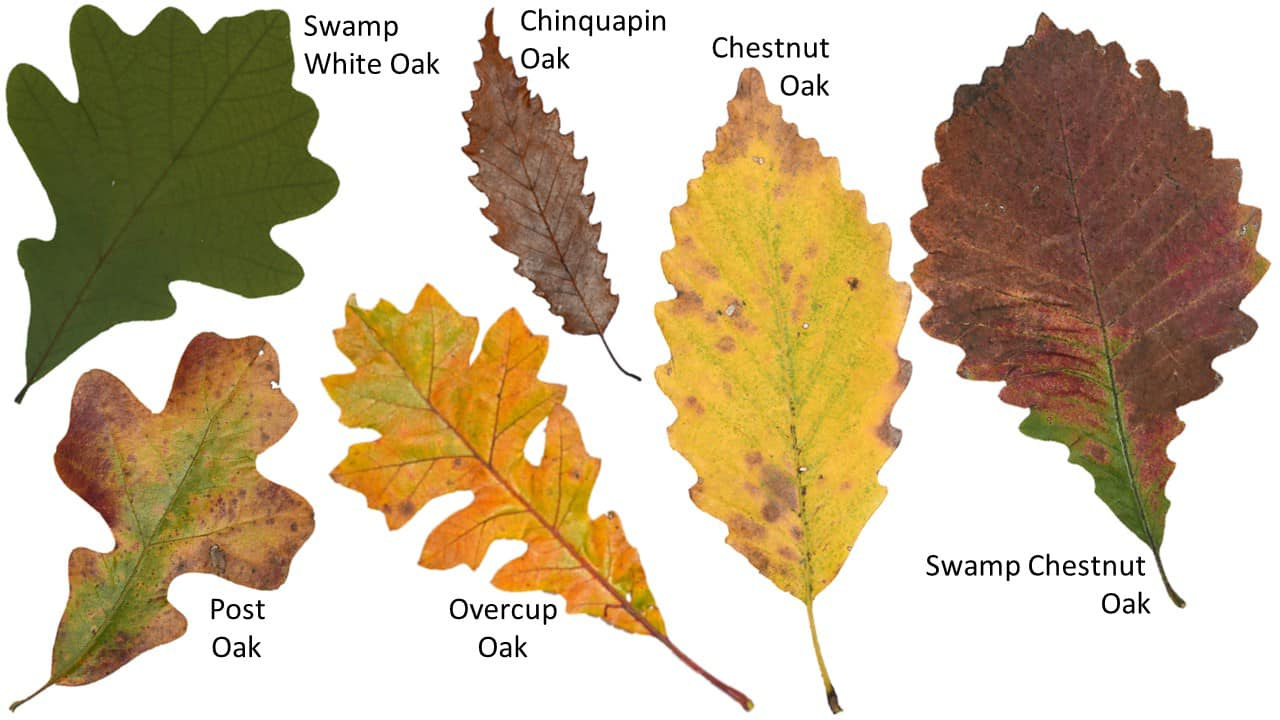

Chinquapins vs. Oaks

The various species of oaks (Quercus spp.) that resemble chinquapins, by the grace of god, are all white oaks. A sigh of relief is warranted here.

Just for ultimate clarity, there are a couple of specific species with these names— so there’s a group that falls within the group of white oaks, but the White Oak (Quercus alba) is just one member thereof. Likewise, red oaks are a whole group of several species, but you might hear of the Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra) or the Southern Red Oak (Quercus falcata), which are both particular members of that group. Those species are individuals within those groups, but the group includes far more than just them.

Hopefully that makes sense; here’s a visual representation courtesy of iNaturalist:

Our two groups of oaks— white and red— are visually disambiguated by whether or not they have bristle tips on the teeth that line the edges of their leaves. If there are tiny bristles, you’re looking at something in the red oak group. If there are not any, you’re looking at something in the white oak group. Chinquapins will resemble red oak group species in that they do have bristles as well.

So, if you’re trying to tell the difference, similar-looking white oaks will lack bristle tips (because they’re in the white oak group) while chinquapins will have bristles.

The aptly named Chinquapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) is the one you’re most likely to confuse with a true chinquapin. Its name just means it looks an awful lot like a chinquapin. They are not equivalent at all, and are in a separate genus.

As you can see above, the tips of those leaves are simply rounded into teeth. There’s no needle-like tip projecting off of them.

By contrast, here are some chinquapin leaves with the bristle tip:

Oh, and another easy tell: chinquapins have nut cases that are covered in spikes. Oaks have, well, normal little acorns (surprising, I know).

By the time fall rolls around and the fruit are visible, it’s pretty obvious.

They also have very showy flowers, comparatively.

Oaks will have droopy tassels that are yellow and come out in very early spring, when little else is green. Chinquapins resemble Bugles (the chip) (sorry, I compare so many things to this…) in shape, are white or cream toned, and can be almost a foot long. They like to curve upwards towards the sun, and will flower around May or June, once it starts routinely getting hot out in our area.

Personally, I think they have a quite attractive (if not nearly-exotic) appearance.

I don’t have any flowers of Chinquapin Oak (Querus muehlenbergii) to compare with, but they’re probably roughly similar to these pendulous (think of a clock pendulum) flowers from a Blackjack Oak (Quercus marilandica):

Of course, although chinquapin flowers look quite different from oaks, they also look similar to the other chinquapins and chestnuts.

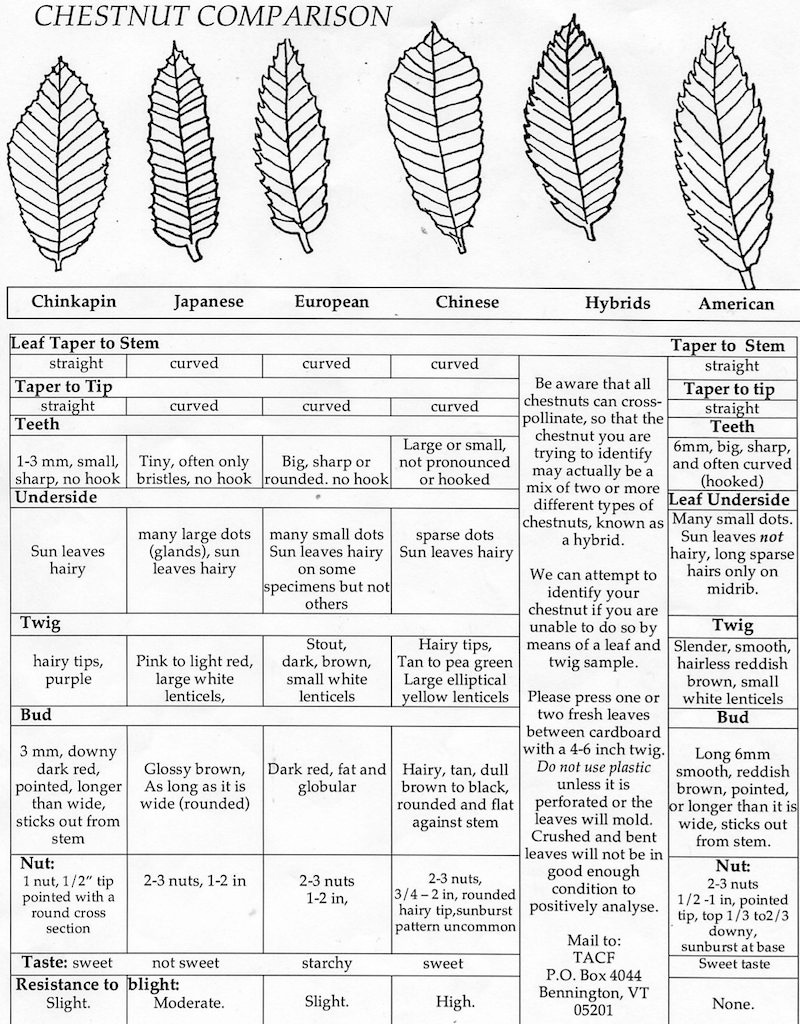

Chinquapins vs. Other Chestnuts

Throughout this article, I’ve been referring to chinquapins generically. In the Ozarks, we only have one chinquapin— the Ozark Chinquapin (Castanea ozarkensis)— so I’m doubling up a little bit here. There are other chinquapins, and other chestnuts.

For ultimate clarity, there are two chinquapins in Arkansas. We also have the Dwarf or Allegheny Chinquapin (Castanea pumila), but you’re really only likely to see that in the southern reaches of the state. If you are like me and live somewhere far north of Little Rock, don’t count on seeing it at home.

Okay, so, what differentiates a chestnut and a chinquapin?

Well, Dr. Paillet mentioned that the accepted definition is that a chinquapin has one nut per case, while chestnuts have several nuts embedded in each hull. However, this is complicated by the fact that chinquapins sometimes break this rule, producing multiple nuts.

The exact definition may be more semantics and culture than true taxonomy, but the names we’ve ascribed to these plants certainly represent distinct entities.

That being said, size matters:

You probably will only see these species in cultivation, so they would be planted near a home or business. Generally, they won’t be in the middle fo the woods.

Beyond our Ozark and Dwarf Chinquapins, there is an American Chestnut. This species is significantly larger, both in the leaves and burrs.

Beyond the American Chestnut, there is also a Chinese Chestnut, which is even larger than the American species… and a whole host of additional exotic chestnut species that people plant!

Here’s a comparison chart with photos instead of illustrations.

It’s kind of complicated, but if you’re looking at a tree that doesn’t seem quite right for a chinquapin, your best bet is to look up Chinese Chestnut identification and go from there.

This page compares all of the species.

Some efforts to restore chinquapins and chestnuts in the United States have involved attempts to cultivate hybrids of the Chinese Chestnut and our native species. The hybrids have a resistance to the blight fungus, but are “half-breeds” with traits of both species— it’s unclear how this mixture of genetics impacts pollinators and the animals like turkeys that consume the nuts.

Other organizations have kept the indigenous DNA of chinquapins alive, like the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation, which is based out of northeastern Newton County, Arkansas.

For only $30 annually, they offer a membership with the benefit of seeds collected from “parent trees… [that are] large 100% pure Ozark chinquapin trees that exhibit varying levels of resistance” to the blight. If you live in the Ozarks and have acidic soils (like those prominently possessing chert, prevalent in northern Benton County and further east) in your woods, this is an exciting opportunity.

Finale

Ozark Chinquapins are a dying breed. As to whether the species will ever bounce back, whether from blight-resistant individuals or from hybridizing efforts, nobody yet knows. Several foundations exist to help keep the foothold this tree has on our planet after it was nearly eliminated by the carelessness of humanity. All I can say with certainty is, I’m infinitely grateful to have access to people who are keeping knowledge of this treasure of a tree alive at least in memory.

There are still several more trips being organized by the Ozark Chapter of the Arkansas Native Plant Society this spring! View the current list of events here. As always, non-members are encouraged to come; there is no cost and you do not need to be a member to attend.

The Arkansas Native Plant Society promotes the preservation, conservation, study, and enjoyment of the native plants of Arkansas, the education of the public regarding the value of native plants and their habitats, and the publication of related information. Memberships start at just $15 per year, with funds going directly to scholarships for student researchers with projects pertaining to native species, and to our biennial meetings where we educate members on native plants and the broader communities they exist in.

Our upcoming meeting is May 2nd-4th in Monticello, Drew County, Arkansas, and you can read our newsletter archive here. If you have any questions about joining, feel free to reach out to the treasurer (me!) or other board members.

I’d noticed that the allegheny chinkapins near me were truly evergreen, unlike C. ozarkensis. Is that the same in North Arkansas?