Glade Hopping Through North-Central Arkansas // May 2025

Start off the day in the full sun, ending the day almost halfway submerged in a stream.... probably the ideal way to spend a day, in this weather.

It’s hard to begin this one— I can’t say what the target plant was, both because we didn’t find it, and also because I don’t want to give any hints about the location of something rare. What I can say is this: all of the other species of the day were infinitely more interesting than a variation on something I’ve already seen several times.

The first stop of the day was a roadside near Yellville, county seat of Marion County, which I’ve never been to before.

There’s only one location I know this species to be at, and I wasn’t able to find it in flower this year, so it was worth the pull-over alone for that… but there was far more to see than just the Purple Beardtongue (Penstemon cobaea).

In a matter of minutes, I was introduced to three new species. Andrew and I both incorrectly guessed that this mat-forming plant was likely something in the Euphorbiaceae, given its habit being similar to some Croton spp. and its habitat clearly being, well, desert-like in a glade sense.

Surprise, it’s an aster! This is Flat-head Rabbit Tobacco (Diaperia prolifera).

There are three species in the genus, all of which are pretty rare in Arkansas, although this is the most common one here. As you can see from its wooly leaves, this plant is more common in the true deserts of the country, although it lives in some of our Ozark glades under hydroxeric conditions.

They mostly grew in the parts of the glade that had nearly no soil at all, where bedrock was exposed in large chunks; it seemed to be sensitive to water-retention, which would make sense.

Another desert plant on the glade: Shaggy Dwarf Morning-glory (Evolvulus nuttallianus).

Its flowers seem to be borne on the lower part of the plant when in bud, but face the sun once in bloom. I would end up seeing this same plant on some glades in the Oklahoma Ozarks just two days later, where I saw it in full flower— tragically, with only a cell phone to photograph it— grateful to have learned about this plant at just the right time.

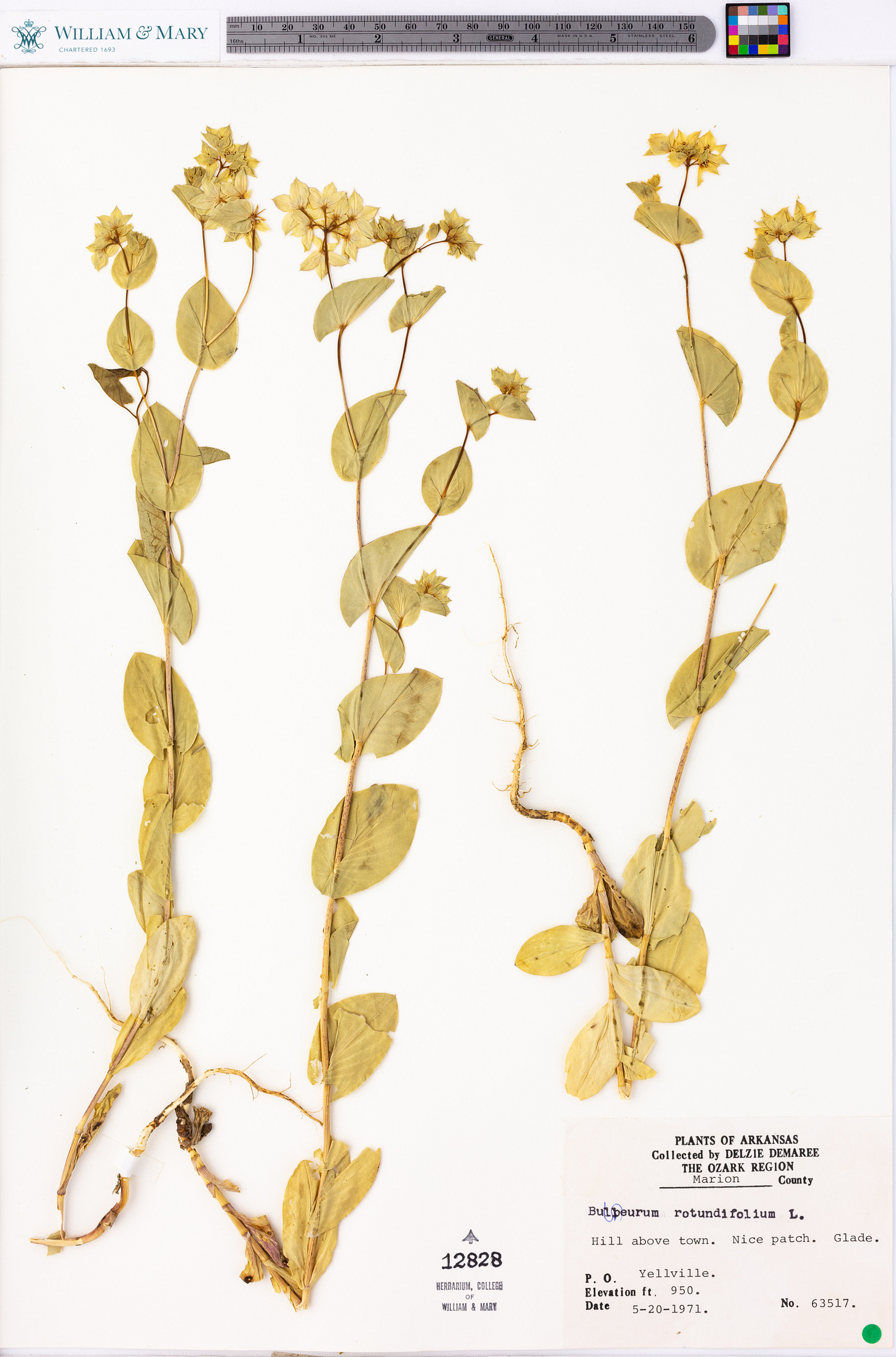

Another failed guess at Euphorbiaceae was this plant— I don’t think anyone in the central US could look at something like this and think “yeah, definitely Apiaceae.” Its flowers resemble Euphorbia species, but they were wildly unfamiliar to both of us, which was a clue that they belonged to a different taxonomic category.

Thorow-wax (Bupleurum rotundifolium) is present all over the sides of Highway 412, at least in the area near Yellville and Crooked Creek, and yet there was only a single observation in the entire state of Arkansas of it on iNaturalist.

Herbarium specimens of it are surprisingly plentiful, and it’s been collected as far back as the 1940s— a good reminder that digital records may or may not overlap depending on source. Some species have been physically vouchered for decades but not posted to first-hand photograph-based accounts like iNaturalist, while others have never been collected but are commonly seen on such platforms. The latter situation is a common case for newer invasive species, but as you can see, this one is old news.

Its native range is broadly northern Africa and southern Europe, but it is apparently sometimes planted as an ornamental, where it escapes and becomes a weed.

Then, of course, there were the plants we all know and love but rarely photograph: Coreopsis everywhere providing little rays of sunshine, Delphinium treleasei not far from its cousin Delphinium carolinianum, the sweet-smelling calamint (Clinopodium arkansana, in this case) flowering in large colonies with delicate purple flowers dangling off each individual, and so on. I got a few pictures of the common Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) since it’s so pretty in flower.

After that, we made a pit stop to Norfork, moving onward to Baxter County.

At an overlook near the Jacob Wolf House, we saw the White River from above, and encountered an unusual (at least in Arkansas) species— the Texas Indian Mallow (Abutilon fruticosum). We have a common member of this genus that’s invasive; both plants grow in rocky, ultra dry habitat. The invasive species particularly likes the receded shores of artificial lakes, like Beaver.

It seemed that almost every time we peered over the White River that day, people on elongated Jon boats with flat fronts (and hulls!) sped across the river. I’ve never seen this style of boat in use before, but it is evidently the preferred marine vehicle for the calmer waters of the White. In my ancestral home, V-hulls are the default, and I’ve hardly seen the alternative.

After living many years close to the shores of Beaver Lake, seeing the undammed portions of the White River is bittersweet. As we scrambled across the glades of Andrew’s home country, I couldn’t help but wonder how similar my own would be, were it not for half of it being forced underwater in the 1960s for the sake of “development”.

After that, we were off to City Rock Bluff. In the more open habitat, we saw a roadrunner not long after Andrew mentioned that they’re a frequent sight in the area.

I was taken aback immediately by the blast of dense colonies of sunflower-yellow succulents across the glade: Yellow Stonecrop (Sedum nuttallii), crossing off the only species in this genus that I haven’t seen yet, and Arkansas Calamint (Clinopodium arkansana).

Only a small number of other plants poked out through the sedum, like a handful of cacti (Opuntia spp.) and some fameflowers (Phemeranthus sp.) that were not in flower yet. The soil was practically non-existent, and the species diversity was quite low; large patches of a single species persisted in sprawling clumps.

Every time I come somewhere like this, I wonder how much of what’s in front of me is a relic of the management style— the details of the way fire is used (timing, severity, frequency), and so on— and how much is the true nature of the area. City Rock Bluff is dense with weeds, like Rumex acetosella and other invasive species, which also grew in clumps only with their own kind. I’ve also never seen a glade with so many broad expanses of uninterrupted bedrock.

Out on the main bluff, a stunted Blackjack Oak (Quercus marilandica) sits sentinel over the White River.

We walked along a wooded edge to get to another part of the glades, stopping to look at several grasses— Dichanthelium, something that looked like Aristida but wasn’t, Festuca octoflora, and so on.

Looking down the slope, I spotted an Ozark Chinquapin (Castanea ozarkensis) in flower, an odd sight.

Most trees in this genus are too debilitated by an invasive fungus— the chestnut blight— to reach maturity, flower, and reproduce. Of those that do, they often bloom only once or twice before perishing, depleted of energy.

I wrote about this species recently here:

Ozark Chinquapins with Dr. Fred Paillet // OCANPS Field Trip: 26 April 2025

We’re about halfway through the scheduled spring hikes for the Ozark Chapter of the Arkansas Native Plant Society, with today’s hike being a rescheduled one, unsurprisingly one orginally cancelled due to rain— better to have too much of it than too little, right?

The stone features on this other glade were interesting, but floristically it was quite similar to the other areas.

The most unusual feature was a liverwort that we found again across the road.

Andrew had just said that he wished he had a telephoto lens, and I made sure to jokingly admonish him for that— it was a major struggle to photograph this nearly-flat plant with an oversized lens that requires a lot of distance from the subject. There are pros and cons to each lens type, and changing between them in the field is a pain.

Several grassland bird species were present at the bluff— Yellow-breasted Chats called and fussed frequently, a lone Bobwhite Quail sang every now and then, and several Red-headed Woodpeckers flitted about the dead pine trees.

The glades on the other side of the road had a large patch of calamint in full flower. Sadly, they were scarred by four-wheeler tracks, and the thin soil had deep trenches carved into it, far deeper than you would guess they were from looking at a distance.

Calamint is the star species of Ozark glades, in my opinion; you can smell it throughout much of the year, and even once you exit a glade, your hiking boots often retain the minty scent. On occasion, it is pungent enough that driving through glade-y areas with your windows rolled down will radiate enough of those oils upwards that you can smell them from your car!

It is strange to be on the barrens, balds, and glades of the Ouachitas and rarely smell anything minty. Out here, it is a dominant species, growing clonally, often spreading from stolons.

Our next stop was, well, a ton of little stops around Calico Rock. Certainly not the best time to visit, but we stuck to the main roads, and only got out for an extensive period of time within the bounds of a park that was quite populated.

We stopped at an old cemetery that wasn’t terribly interesting in terms of plants, but did have this massive Amanita that was nearly the size of a tombstone.

On a random roadside, I spotted some prickly poppies and demanded, with no protest, that we pull over. Man, they were beautiful.

It’s unclear whether the populations of Argemone species in our state are transplants or wild, but either way, they’re stunning. I have fond memories of seeing them in their main range in Texas.

At a few creek crossings along the way, we spotted Spigelia marilandica and other familiar riparian species.

After spending so much time in the dry, full-sun glades, we went further south into low-lying woodlands and ravines, eventually wading through the water in blind pursuit of the target species that we never quite found. On the road down, there was quite a bit of Wild Hydrangea, and even a bit of Goat’s Beard (Aruncus dioica).

The most common species of these seeping ravines was easily Black-veined Maidenhair Fern (Adiantum capillus-veneris). The water levels must be consistent in some parts of these creeks, for the edge where the water met the air was lined with ferns.

Wading through the creek, we saw two types of Indian plantain— the roughly deltoid Arnoglossum atriplicifolium that has leathery leaves with silvery undersides, and the round, pumpkin-leaf-like Arnoglossum reniforme.

Andrew spotted an invasive fern, Fortune’s Holly-fern (Cyrtomium fortunei), growing on one limestone shelf that was otherwise covered in natives like columbine. He promptly ripped it out and shredded it once I told him what it was.

If you ever come across this species, or Cyrtomium falcatum, I will say: they make decent houseplants— pull them out by the root to make sure they don’t come back, though. Definitely invasive.

Some of the bluffs looming over the creek were incredibly dry— large cacti sprawled and spilled off of their edges, spiked paddles dangling over the edge. A small colony of Prairie Dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum) clinged to the edge of one shelf; various goldenrods (Solidago spp.) grew along similar ledges quite commonly.

Cedar trees sprouted everywhere, some upright while others leaned with gnarled, bone-colored trunks that have been bleached from the oppressive sunlight, their green needles draped in cobwebby beard lichens (Usnea sp.).

My favorite bluff sight had to be this massive cactus, with a tiny individual behind it— was that a paddle that broke off and rooted itself nearby, or the original plant that severed? Who knows.

Every now and then along the creek, a Fringe Tree (Chionanthus virginincus) would appear with comparatively plain leaves against the rest of the forest. I only realized what they were once I saw a few with pedicels, their flowers having fallen off a long time ago.

We walked back along a trail that was laden with limestone seeps. The water seemed to appear from nowhere, glimmering and falling down in sheets, carving gentle waves as they rolled downward. Where there is moisture and shade, there is bound to be spring ephemerals and all of their compatriots; this area was no exception.

Bloodroot, False Solomon’s Seal, Ozark Green Trillium, and a few other early spring flowers were present, too.

On the sunnier side of the limestone shelves, those spaces that were not shaded and protected by stone, there were some normal woodland species as well.

I was surprised to see a ton of Carex eburnea in the area; it reminded me a lot of the dolomite woodland-glade matrix around Lake Leatherwood, over in Carroll County (quite a ways away from here). It is one of my favorite monocots.

As we made our way out, there were several small Ozark Chinquapin saplings growing, some Ceanothus americanus, and even some Strawberry Bush (Euonymus americana). We ascended out to the highway, driving through dense plantings of Short-leaf Pine, and from there we were on our way home.

What a blessing it is to have a friend that you can spend a solid twelve hours with and not get tired of.